studio journal & news

an evolving archive by artist Alexander James Hamilton.

Journal

The Long Arc of Value: How Photographs Gain Imp...

Photography has always sat at an unusual intersection in the art world. It behaves like a reproducible medium, yet the works most valued by museums and collectors are those tied...

The Long Arc of Value: How Photographs Gain Imp...

Photography has always sat at an unusual intersection in the art world. It behaves like a reproducible medium, yet the works most valued by museums and collectors are those tied...

A studio designed Morpho blue butterfly wallpaper

Designed with Morpho Peleides, Morpho Amathonte, Morpho Adonis and Morpho Rhetenor Adonis butterflies finished in a flock silk finish and a pearl ink finishing layer. a close up of the...

A studio designed Morpho blue butterfly wallpaper

Designed with Morpho Peleides, Morpho Amathonte, Morpho Adonis and Morpho Rhetenor Adonis butterflies finished in a flock silk finish and a pearl ink finishing layer. a close up of the...

recycling aluminium into a beach inspired range...

A full video showing the process I use to make these wonderfully tactile bathrrom & kitchen door 6 drawer handles from recycling aluminium. 3d split moulds, recycling aluminium & sand...

recycling aluminium into a beach inspired range...

A full video showing the process I use to make these wonderfully tactile bathrrom & kitchen door 6 drawer handles from recycling aluminium. 3d split moulds, recycling aluminium & sand...

the first carbon neutral recycling studio tackl...

WELCOME TO MAKERS PLACE - a brief introduction to this project that helps oceans stay clean for habitat & species protection from pollution. Makers Place II is already underway, join us...

the first carbon neutral recycling studio tackl...

WELCOME TO MAKERS PLACE - a brief introduction to this project that helps oceans stay clean for habitat & species protection from pollution. Makers Place II is already underway, join us...

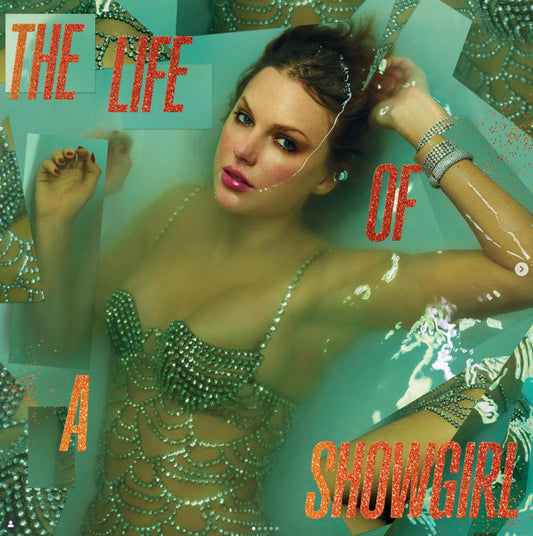

Taylor Swifts ´The Life of a Showgirl´, after O...

World Photography Day, Ophelia, and the Importance of a Singular Print 19 August 1839 is often called photography’s birth certificate, the day François Arago publicly disclosed Louis Daguerre’s process to the...

Taylor Swifts ´The Life of a Showgirl´, after O...

World Photography Day, Ophelia, and the Importance of a Singular Print 19 August 1839 is often called photography’s birth certificate, the day François Arago publicly disclosed Louis Daguerre’s process to the...

´ Goya Reborn In Water ´ an exhibition inside t...

PRESS RELEASE... ´ Goya Renacido en el Agua ´ Castillo de la Piedra Bermeja, Brihuega.open from 5th July until 30th September 2025. July open 7 days a week 11-2pm & 5 to...

´ Goya Reborn In Water ´ an exhibition inside t...

PRESS RELEASE... ´ Goya Renacido en el Agua ´ Castillo de la Piedra Bermeja, Brihuega.open from 5th July until 30th September 2025. July open 7 days a week 11-2pm & 5 to...

Floral Vanitas Drop - Unique Prints From A Limi...

I am delighted to present this rare drop of 100 floral Vanitas prints, each unique print ordered will be selected at random from the collection and shipped direct. Available in either one...

Floral Vanitas Drop - Unique Prints From A Limi...

I am delighted to present this rare drop of 100 floral Vanitas prints, each unique print ordered will be selected at random from the collection and shipped direct. Available in either one...

A guide to building a photography collection

Photography is one of the most exciting and accessible mediums to collect. Whether you are looking to find and champion emerging photographers or head towards the most collected names of...

A guide to building a photography collection

Photography is one of the most exciting and accessible mediums to collect. Whether you are looking to find and champion emerging photographers or head towards the most collected names of...

A WaterGate scandal in the French water industr...

For over four decades I have raised the alarm about the bottled water industry, and how it sells little more than filtered tap water wrapped in illusion. Now, even the...

A WaterGate scandal in the French water industr...

For over four decades I have raised the alarm about the bottled water industry, and how it sells little more than filtered tap water wrapped in illusion. Now, even the...

exploring the physics & mechanics of light caus...

In optics, light caustics are patterns formed by the concentration of light rays reflected or refracted by curved surfaces or objects. These patterns appear as bright curves or surfaces where...

exploring the physics & mechanics of light caus...

In optics, light caustics are patterns formed by the concentration of light rays reflected or refracted by curved surfaces or objects. These patterns appear as bright curves or surfaces where...

Circular lighting range designed by humans and ...

This lighting range is thoughtfully designed allowing for material integrity with an emphasis on tactile qualities, functionality in an enduring form. Designed and manufactured to make them affordable to as...

Circular lighting range designed by humans and ...

This lighting range is thoughtfully designed allowing for material integrity with an emphasis on tactile qualities, functionality in an enduring form. Designed and manufactured to make them affordable to as...

Exhibition ´Renaciendo´ an academic text ´Creat...

Original text in Spanish, English translation below.... RURALISMO CREATIVO: EXPOSICIÓN DE ALEXANDER JAMES HAMILTON ´RENACIENDO´Javier Poyatos Sebastián Profesor Titular de UniversidadTeoría de la arquitectura y la ciudadUniversidad Politécnica de Valencia.Una muy...

Exhibition ´Renaciendo´ an academic text ´Creat...

Original text in Spanish, English translation below.... RURALISMO CREATIVO: EXPOSICIÓN DE ALEXANDER JAMES HAMILTON ´RENACIENDO´Javier Poyatos Sebastián Profesor Titular de UniversidadTeoría de la arquitectura y la ciudadUniversidad Politécnica de Valencia.Una muy...